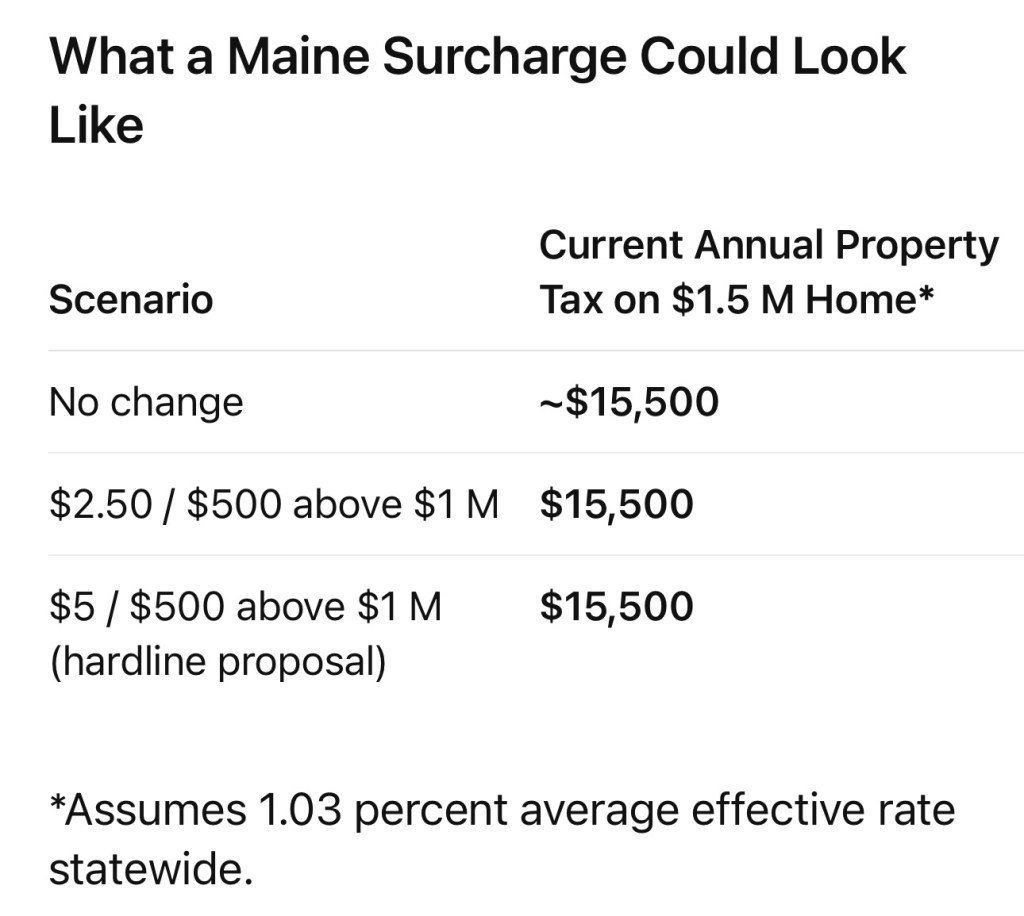

Rhode Island lawmakers just dusted off their so-called “Taylor Swift Tax,” a surcharge aimed at luxury second homes valued above $1 million. At $2.50 per $500 of assessed value beyond that threshold, the proposal could tack six figures onto an annual tax bill for the likes of Swift and other high-end owners. Make no mistake: it is less about pop stars and more about the widening gap between local buyers and absentee ownership across New England.

That spotlight now turns to Maine, where more than 157,000 homes—over 21 percent of the entire housing stock—sit vacant. Many are ski chalets, lake camps, or coast-view retreats held by part-time residents. As a developer who also happens to be building a primary residence in Newry, I am watching the debate with a personal stake. If Maine imports a version of Rhode Island’s levy, my construction budget and carrying costs could jump overnight. It has me eyeing Vermont’s friendlier policy climate as a real alternative.

Why Maine Is Vulnerable

Second-home saturation. A 2019 IPX 1031 study already crowned Maine number one for second-home share. Pandemic buying only deepened that lead. Inventory rising, affordability static. Realtor.com® shows a 27 percent surge in active listings from January to March 2025, with seasonal hubs like Kennebunk and Naples tripling month-over-month supply. Prices, however, have barely softened. Local tax strain. Municipalities facing higher service costs see a revenue gap. Targeting non-primary residences is a tempting fix.

That combination makes a vacancy tax politically attractive. Full-time residents wonder why they should shoulder the same mill rate while competing for housing they cannot afford. Policymakers read the polls and look for quick wins.

Stretch those numbers across construction loans, escrows, and future resale comps, and the financial case for building in Maine loses some shine.

Newry vs. Vermont: A Personal Calculation

I chose Newry for proximity to Sunday River and the ability to prototype sustainable-design elements that inform my larger multifamily work. Yet Vermont, with its Act 250 reforms and a legislature currently dialing back talk of vacancy levies, suddenly looks more predictable.

Key considerations:

Permitting timelines. Maine’s surge in seasonal inventory means local boards may tighten environmental and density reviews. Vermont, by contrast, is centralizing approvals to accelerate housing starts. Tax exposure. If Augusta mirrors Providence, carrying costs on a Maine build could rise by double digits. Vermont’s current debates revolve around broader income-tax relief rather than property levies. Exit liquidity. A punitive second-home tax risks chilling the luxury-buyer pool in Maine, squeezing resale values just when construction inflation is stabilizing.

Takeaways for Developers and Investors

Policy risk is now a primary underwriting variable. Overlay potential vacancy or second-home taxes when modeling returns in destination markets. Local engagement matters. Sponsors who partner with municipalities on workforce or year-round housing can mitigate political blowback. Diversify exposure. Balancing holdings across states with differing tax trajectories protects both LP capital and personal assets.

For my part, I am not abandoning Newry yet, but the blueprint is under review. If Augusta moves toward a “Swift Tax,” don’t be surprised if the crane and crew end up breaking ground across the Connecticut River instead.

Daniel Kaufman

Opinions are my own; numbers are approximate. For detailed underwriting guidance, reach out anytime.

Leave a comment