The numbers are stark. The National Low Income Housing Coalition puts the U.S. affordable-housing shortfall at seven million homes, while Fannie Mae pegs the workforce-housing gap at 2.2 million units. Vacancy in income-restricted rentals hovers near 2.7 percent—less than half the vacancy in Class A apartments. Nowhere is that crunch more acute than in ski towns, where hourly staff compete against deep-pocketed second-home buyers and short-term-rental investors.

Vail just decided business as usual is no longer an option.

Why This Project Matters

On a scrubby parcel between Red Sandstone Elementary and Middle Creek Apartments, site work is underway for what will become 268 deed-restricted rental homes—84 studios, 100 one-bedrooms, 84 two-bedrooms—plus 257 podium parking stalls. Every lease will require at least one full-time Eagle County worker to live on-site. Construction ramps up in September 2026, and leasing is scheduled to start three years later.

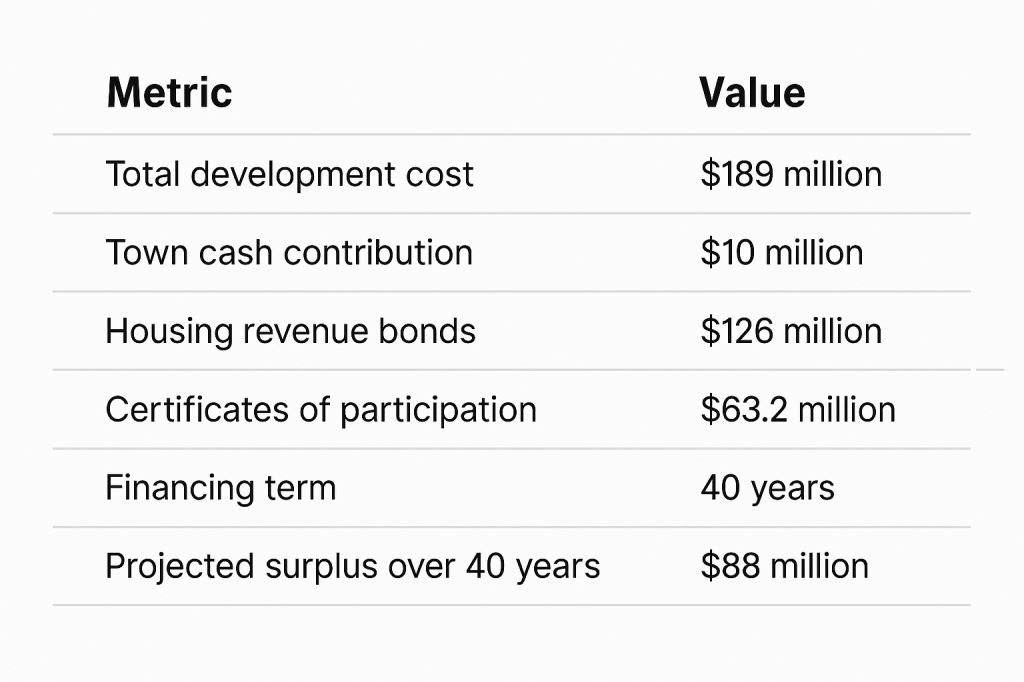

For a resort town of Vail’s size, the scale is unprecedented:

The council paired $10 million in equity with a May bond sale that locked in long-dated debt. Interest payments will be steep—$366.7 million if nothing is refinanced—but rent proceeds are modeled to cover debt service, operations, reserves, and still throw off cash. In other words, the town is trading balance-sheet capacity today for housing security tomorrow.

Takeaways for Real-Estate Professionals and Investors

Public-sector capital stacks can pencil. By combining cash, revenue bonds, and COPs, Vail spreads risk while maintaining ownership control—a template worth studying for other municipalities that sit on under-utilized land. Durable demand underpins the pro forma. With vacancy below three percent across deed-restricted stock, collections should remain resilient through cycles. Long-run upside still exists. The twenty- and thirty-year cash-flow projections leave room to refinance once rates normalize, enhancing overall IRR. Community buy-in beats NIMBY drag. Vail held public naming workshops (finalists: Southface and Vailvue) and framed the project as core to the guest experience—critical for avoiding delays.

What It Means for Skiers

Better staffed lifts, shorter lunch lines, and locals who can actually afford to live where they work. When employees spend less time commuting over icy passes, service quality improves and the après scene regains the energy many of us remember from Vail’s early days.

Part of a Broader Colorado Push

Vail is not alone. Rifle’s 60-unit LIHTC community, Aspen’s 300-unit Lumberyard initiative, and Breckenridge’s net-zero Runway Neighborhood all prove that mountain towns are leaning in on attainable housing. Collectively, these projects show how local governments, mission-driven developers, and private capital can align to solve an urgent problem while still meeting return hurdles.

Final Thoughts

Ski resorts thrive when lifties, patrollers, bartenders, and teachers live close enough to invest in the community they serve. Vail’s workforce-housing project is ambitious, but ambition built this valley in the first place. If you develop, broker, or invest in resort markets, keep a close eye on Vail—its success, or failure, will shape the model for the next decade.

Stay tuned here at DanielKaufmanRealEstate.com for field notes from the front lines of housing innovation in America’s mountain towns.

Leave a comment